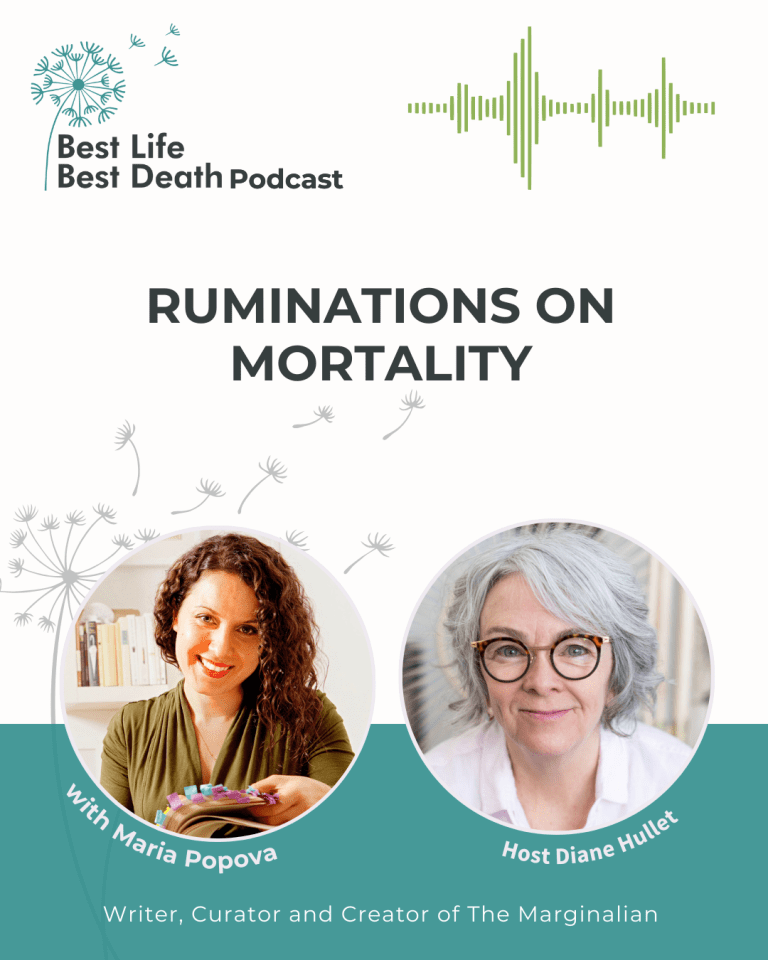

Maria Popova is a Bulgarian-born writer, curator, and critic best known as the creator of The Marginalian (formerly Brain Pickings), a long-running online publication exploring art, science, philosophy, and the human condition. What a treat to talk with her on this episode about birthdays, mortality, meaning, “un-selfing,” nature, daily practice, and the big questions that lie in the substrate of all human lives. How often do you get to think alongside a modern-day philosopher who believes that mortality drives everything we do?

Transcript

Diane Hullet: [00:00:00] Hi, I am Diane Hallett, and you’re listening to the Best Life Best Death podcast, and today I’ve got a wonderful guest joining me, somebody that I guess I got to know through. I don’t know, someone probably sent me one of her projects, one of her newsletters. Although it’s so much more eclectic than that, we can’t even limit it in that way.

So welcome to Maria Papova.

Maria Popova: Thank you Diane. So wonderful to be part of your beautiful project.

Diane Hullet: Well, thank you and so wonderful to be a part of yours. Tell us, you know, tell us a little bit about how you describe what you do as an artist and a thinker and a philosopher and a curator of ideas.

Maria Popova: Well, it’s interesting because from the interior, I feel like none of those things, I feel like a person learning still how to live.

And you know, I started. This [00:01:00] what record, this written record of my understanding of life. When I was in my early twenties, I had come to the US from Bulgaria, sold on the premise of liberal arts education, which presumably teaches you how to live. And instead, I found myself in this factory model of standardized testing.

You know, the 400 person lecture hall with the professor and the PowerPoint slides and none of it, none of it, helping me figure out how to be a human being. And meanwhile, you know, working four jobs to put my way through school, completely disoriented by the culture shock. So I just very, very blindly started reading on my own.

At the library online, pulling out Aristotle and volumes of, uh, Japanese woodcuts from the 18th century, all these things, and just keeping a record of, of that. And, and I, at the time it was called brain picking. I wrote it for myself. I shared it with, there were [00:02:00] seven guys that one of my jobs. That it became kind of an internal email for inspiration for our little team, and that was, that was that.

That was almost 20 years ago and it hasn’t. In, in purpose. It hasn’t changed in texture. Of course it has because the person that’s helping live, I mean, I’ve changed, uh, thank God, uh, a whole lot since I was my twenties. But, uh, and to this day, that’s what it is. And the seven people, or many strangers now, millions of people around the world, but uh, I think we’re all reckoning with just about the same basic questions.

When you dig. Deep enough under any particular human experience that there’s substrate that’s pretty universal and, um, we’re grappling together.

Diane Hullet: Oh, I love this. The universal substrate. Yeah. Yeah. That’s so good. I don’t know who first sent me a copy, and it probably was back when it was called Brain Pickings, [00:03:00] but now it’s called The Margin Alien.

Am am I saying that correctly? That’s like, um,

Maria Popova: you know what, it’s so funny that it, it almost doesn’t matter how you say it. I, I. After 15 years of, I mean, bear in mind I had come to the us English was my second language as a young person. In a new language. I loved puns and plays on words, and I named it on a whim on a Friday afternoon in Philly and whatever day it was, October, 2026, and proceeded to hate the name for the next 15 years because it was this kind of cheap word play.

And also because I had started out, uh, very much interested in psychology and neuroscience and. That is a very Cartesian way of thinking about human experience. It’s all the brain and the mind. And over time I came to a much more embodied and integrated approach to life and it felt so limiting to call it brain pickings.

So anyway, I called it marginality and because it is essentially my [00:04:00] marginality on what I read in order to to live.

Diane Hullet: Yes. Yes. And what’s so wonderful about it is each of your emails, I, it pops in my inbox once a week and each one of them connects to previous issues and episodes. And, and so there’s this whole weaving of art and life and philosophy and writings and old writing and new writing and poetry and videos, and it’s, and it’s bite sized, you know, that’s the other thing I love about it.

So I got really intrigued about. What, probably a year ago you, uh, kept putting up, maybe two years ago now, you kept putting up these absolutely gorgeous little collages that were like a, like a old Bird Almanac painting with almost like magnetic poetry. Remember that from refrigerator? Mm-hmm. We didn’t have

Maria Popova: that in Bulgaria.

That was a very exciting thing to discover as an adult in America.

Diane Hullet: Like you were like, what? There’s poetry magnets. So it was like that kind of old type font. And you were making poems on top of these birds, [00:05:00] and then you said, yeah, that’s me making those. And um, yeah, I’ve actually made 40 of them one a day for my 40th birthday and given them to friends.

So when I was turning 60 this past year, I, I was like, I think that’s kind of interesting. I think I’d like to take 60 of something and part of what I, I loved that you made one a day and in that you could really see this like evolution. And I just found it fascinating, like my creative life process, just so much more.

Um, it just, I, I wasn’t able to be that linear, right? Mm-hmm. So I’m like 20 at a time or 10 at a time. And, um, but you very much inspired me. And so for my 60th birthday, I sent out 60 little collages to people. That’s so wonderful. It was so wonderful. It was so fascinating. And then recently, you said you’re making another project for your 41st.

And tell us about that.

Maria Popova: Well, I wanna say something that I think is a very important difference between your [00:06:00] approach because you were making art, you were making, you had a creative practice for the purpose of, you know, giving these gifts to friends that were art. I, uh, this thing with the birds started so mysteriously to me and it, it was the way of.

Clarifying my own mind. I didn’t know what I was gonna do with them. I just, every day was very soothing to me. The way I make them is at night. I look visually through a 19th century ornithological book for. A bird painting of a bird that calls out to me. I’m using mostly Audubon Gould and kind of the, the grates of Ornithological illustration.

Then I read the text in the book about the bird. The ornithological text for the first one I made was The Great Blue Heron. John James Audubon wrote 10 whole pages on the Great Blue Heron. I mean, this is scientific text. Of course. In the 19th century, the scientists were really poets. They were educated in a much more holistic way.

Talk about the liberal [00:07:00] arts. You know, promise and premise. They lived it. So they were beautiful writers. Of course, that’s a cheat. But anyway, I would read the text and I would let words jump out at me based on whatever I’m reckoning with that day. I would circle them and slowly I kind of sentiment would start to emerge from the text.

And once I had the skeleton of. What it is, the, the concept could be friendship or love or death, or, you know, whatever that day was on my mind. Then I would kind of fill it in with other words from that creative constraint of the essay. So, in a way, I, I actually don’t think I was making art. I think was in a conversation with my own unconscious, through the medium of, you know, existing materials, creative constraint and all of that.

But it, and I wouldn’t call them poems, they look like it because. Their line breaks there, you know, there’s, there’s a shape to it. Uh, but they are, to me, uh, these strange, uh, divinations of [00:08:00] my own mind grappling. Records of grappling.

Diane Hullet: Oh, I love that. Records of grappling because that’s, it seems like as a human, that’s what you really do.

You like to grapple with Yes. Words and concepts and how things fit together. And there is this incredible thing about creativity. When it has constraints, it kind of flows in a different way. What a catalyst,

Maria Popova: isn’t it? What a catalyst. Um, and, and the other interesting thing was, uh. Around the time they started coming to me, I, I realized that, you know, I come from a pretty scientific, uh.

Worldview I, I did very intense math as a child. I have been interested in science and immersed in science in the time since. However, I realized that a lot of my close friends who my love and intellectually respect were using tarot tarot cards, which my entire life I’ve dismissed as this anti-scientific blah, blah, blah, medieval.[00:09:00]

And then I came to see, oh, they are just a language of self interpretation. We need because we are half APA to ourselves. Consciousness is just this extraordinary quicksilver mirror with, you know, the, we only see one face of, and there’s so much else. And so I thought, okay, I just to kind of tease my terror loving friends, I would make cards.

I would make a deck of these so-called divinations that are just as abstract as the interpretation of a, you know, predetermined set of. I mean, tarot is a language, uh, uh, existing language that you then interpret in the context of your own life anyway, so that there, there was also that element of the slightly stubborn, let me subvert with weird art or whatever, the existing paradigm

Diane Hullet: of divination.

I love that. I love that. And the almanac of divination was born, which comes in a beautiful box set and um, is extremely lovely. I think it’s. It’s in print now. For a [00:10:00] while it was hard to get, but now I think you can order them.

Maria Popova: Yeah, I mean, what happened, you know, I, on the marginality, and I don’t write personally, I, I reckon with life, but within one or two degrees of abstraction from my personal.

Life. I write about ideas. I draw an existing text. It’s very hard for anyone to know what I’m living through in my personal life. This thing was a one-off that was deeply personal. I shared it on the eve of my 40th birthday in 2024 on a total whim. It was kind of a risk because it was so unlike everything else.

And what happened was I shared some of them in a single essay about the process, showed some of the images. I said, I made these for 40 of my friends. I just used the mom and pop printer to print the decks, and then I was flooded. Flooded. I mean, in 18 years of doing what I do, I haven’t heard this much from people about something.

And people were like, where can I get the deck work? And I was like, you can’t, you, it doesn’t exist. [00:11:00] So I ended up making it. And also because by that point I had made for, for my 40th. I had to send it to the mom and pop printer of the decks for my friends by June. But the daily rhythm was so comforting to me that I kept making them after I sent it the printer.

So by August I had a hundred. And anyway, long and short of it is then I decided I, I’ll just make this thing for the world and people will use it as they see fit. So now it’s. Much more oversized deck of a hundred of them.

Diane Hullet: So, so beautiful. So cool. And you’re absolutely right. Mine was, my process was almost more like making little quilts for people.

Like I’m a quilt. Yes. There’s something about when you make a quilt and you know who it’s going to, there’s something very satisfying. You kind of think about that person in the back of your mind while you sew. And this was like that. They were like little tiny collages, mostly made from things I already had like.

Birthday cards I’d torn up or beautiful things. You know, I, I have a little stash of beautiful things, so, you’re right, you’re right. [00:12:00] Different, different process. Because this was more kind of intentional for a single person Yes. Than a process, but

Maria Popova: very similar using existing material. Yeah. Lens through your own consciousness to make something new.

Diane Hullet: Yeah, to make something new and how, how I, I always kind of joke, like I, I don’t do a whole lot of sitting around and I don’t do a whole lot of watching tv. No, no offense to people who love their shows, but I just am, I always wanna be doing something like, I just always find, like, I don’t for that, I’m busy making stuff and the, the capacity to want to make something, whether it’s a, a visual piece of art or a.

A clay piece or a piece of music or something ties you to something and I’m curious what you, you know, what you found. Because I think when I go into those places of creating, it doesn’t even feel like I’m the one creating it. Like I just am following this path. It says, put some blue there. Oh, add some sparkles here.

Well, it’s creating, it’s creating you

Maria Popova: in a way. It’s [00:13:00] creating you. And you’re participating, you’re channeling. Um, I do think, I mean, it’s two things. Uh, for me personally, I’m very prone to rumination, and it is a form of which is a selfing of the mind. It’s a, it’s an inward spiraling that is l losing perspective on the outside world, looking in and in and in and in ultimate selfing.

This kind of creative work takes you out of the mind, and it’s a work of unself. You’re suddenly attending to something else, making something that is externally oriented, but coming from the inside, from the inside out, and really for me, interrupting the ruminative self-referential spiral, that is the basis of most human suffering, actually psychological suffering, at least.

Diane Hullet: Yeah. Yeah. So well said. So your current project is in a different medium. [00:14:00]

Maria Popova: Yeah. I mean, again, I wouldn’t call it a project, it’s just the, the next thing I took up to have this daily rhythm. Yes. This, it is an affirmation of aliveness to show up for something every day.

Diane Hullet: Oh. Oh, that’s so good. It’s an affirmation of aliveness to show up for something every day.

Yeah. Whether it’s putting together the pieces that you put together artistically, or whether it’s putting together the connections of philosophy and ideas.

Maria Popova: Yes. Yes. Uh, now it. Ran its course with me. The way the birds did it, it came, it were with, they were with me for a while and they left just as mysteriously as they came.

And then this year, shortly before my 41st birthday, I took up ceramics, uh, to a point where I was at the. Wheel four hours a day, maybe clay, all over my library, all over my hands, all over my mind. I would go to sleep and think of clay. Uh, and I started making [00:15:00] again for reasons that who knows how many composite inspirations, you know, consulated, this particular thing, making tiny little urns that say around the perimeter, hold on, let go.

And they were, in my mind, the first one I made was the kind of. Uh, symbolic vessel for I, you know, I think birthdays make people on average contemplate a, a, a next phase, another year of life. Look back on what they wanna keep from who they were before and looking forward to who they want to be in the next iteration, et cetera.

I had a very difficult year between 40 and 41 that required me letting go of certain. External things that were reflections of certain internal things, but required. Also, holding on to what makes me me, it’s not always easy to tell the difference between the things that need to go and the things that need to stay.[00:16:00]

And so somehow that became, oh, I’m gonna make a symbolic vessel. Into which to, to stare into the mouth, the cold stone mouth of the earth, the, the urn, and contemplate what it is I need to leave behind and what it is I need to carry forward. And again, I started making one a day every day, numbering the bottom day one, day two, day three, with the idea of then giving them away to people who make my life more livable.

People in my personal life, but I am a real introvert with, with a very small, deep circle of friends. So I don’t have 41 pillars of my life. So I thought the remaining ones I just give away to my readers, and that’s what I’m now in the process of doing. I did a little raffle and uh, I have to mail them now to the.

Chance chosen people who ended up getting an earn,

Diane Hullet: which is kind of an amazing commitment, right? With mail [00:17:00] prices as they are these days, it’s like, oh, I haven’t even gotten there. See, I hadn’t even thought of that. But yes, you’ll have to have a little bubble wrap and wrap them up. Well, there’s something so beautiful.

I, I believe the phrase you used was urns for living. Is that what it was?

Maria Popova: Yes, yes, yes. That, but isn’t this, we are urns for living. Human body is an urn for living. This mortal vessel that we fill with aliveness?

Diane Hullet: Yes. Yes. Is an earned for living. And the whole task, it seems like, is what to let go of and what to hold on.

Right? That’s like a life. Yes. Yes, yes. Talk to me a little bit. Like, say more about how, for you, I, I, you know, a lot of your pieces of, of writing configurations have to do with mortality. What are, what are some of the interesting reflections you’ve come to from that? Oh, well,

Maria Popova: I think everything [00:18:00] only has to do with mortality.

I mean, all creative work, I believe, is a coping mechanism for the fact that we’re mortal, that, uh. There is, we, we are creatures made of time who are suspended between, not yet and never again. This life that we have, it could have never happened. And it will one day never have been. I mean, it will have been, but it will never again be, you know, and I think we make art to, to process the bewilderment of being alive.

Um. So in a way it’s just a matter of how many levels of awareness are we from mortality as the foundation of the creative impulse and of the, of everything. The love impulse we love because we are mortal.

Diane Hullet: Yes, we love, we create, we think, we dream, we ruminate. Yeah. Yes. [00:19:00] You had a recent, uh, connection with, uh, a, a lot about, it was about stars and the universe, and that one was really incredibly beautiful too.

I’m not remembering the exact kind of connections in it, but it was taking these really big universal pieces and connecting them back to your own reflections, your own life. Um, and as you said, kind of a degree removed from your own personal life, but your life as a human was, I thought it was really beautiful.

Maria Popova: Well, thank you. I think, uh. It is impossible to think on the microscopic scale of individual existence without accounting for the telescopic scale of space and time. And this sliver of space time we’ve each been given that we call a life, our life, our little portion chance given portion of space time.

Um. It is very comforting to me. Again, the ultimate unself. If we presuppose that most suffering [00:20:00] is selfing, then Unself coming to meet nature on its own terms, coming to broaden the aperture and take in. This larger reality that so predates us and will post data and includes everything else. To me that that work of Unself is the most potent antidepressant, stimulant.

Vitalizer, all of it. All of it,

Diane Hullet: yeah. And people, it seems like, what are the avenues that you see people use for that unself thing?

Maria Popova: I mean, you know, it’s so, uh. I am, I tend to be optimistic about human nature, but one thing that is just a fact is that I have been writing on the internet for almost two decades, and I have seen the tidal wave.

Uh, first of all of the internet itself is a medium for human thought and feeling what it prioritizes, and then the different styles in which people ride the wave. Right. And. It has veered [00:21:00] more and more toward selfing. Uh, it is now a medium for selfing, partly because our culture has started. I, I find that opinions and identities are the least interesting, least durable, least compelling parts of people.

Um. They have very little, they’re kind of the surface shimmer on this deep ocean of reality and universality and, and, and the, the kind of, the elemental in us gets really, really diluted when we get to the level of identity and opinion. Because it’s mutable, because it’s reactionary, because it’s, uh, subdivided.

You know, any kind of identity is exclusionary. I am. This already says I’m not. All these other things that live in me and anyway, that, that is unfortunately what now our culture. Leads with, and the internet has been a very subservient, uh, [00:22:00] entity to these trends. And, and then reinforcing them, making them even more pronounced.

So this is all to say, I think it’s harder and harder for people to unself the way I see it, both in other people and in myself, myself, is uh. By stepping away from this feedback loop and into the living world, into nature, into reality beyond ourselves. I am here now in a forest. I’m gonna get off this screen and in my face will be the barred owl and the, you know, the little chipmunk that I can even hear now, wrestling there in the leaves and they have lives that have.

No, um, interest in our identities or opinions, and they’re part of this immense ecosystem that we are just this tiny.in. I find that very comforting.

Diane Hullet: Yeah. Isn’t it amazing? I think some people find it very comforting and some people find it very [00:23:00] unnerving, right? To be that separate from their self by immersing themselves in a natural world or a natural phenomenon, and, and it’s.

It’s like laying back and looking at a starlet sky. You either feel immense comfort in that, or immensely insignificant in that, or maybe both at the same time. I know,

Maria Popova: right? I I don’t think it’s an either or. I think it’s, yeah. I mean, we need the self, right? We need the ego in order to move through the world as a functioning entity in order to have decision-making, in order to have taste and preferences.

Communicated all these things. We need the self, it’s a adaptive feature of higher consciousness, but it serves us to a point and then it turns us inward and it actually severs us. From the world. So as long as it helps us move through the world, it’s wonderful. And so looking up at a starlet sky, knowing that each star that you see is actually a star system.

It’s a planetary system. On average, a star has about four planets orbiting it. Every indi [00:24:00] visible universe, every star you look at, you can be assured. It has on average four planets, possible worlds around it. I mean, it is an immensity we can’t even fathom. Of course we’re gonna feel dwarfed, but I think there’s freedom in that smallness.

Diane Hullet: Oh, say more about that.

Maria Popova: It, it is exactly this, that, that the moment we accept we are transient, we are small, we are insignificant, then we have the freedom to just be for the time we are and be what we are. Not perform a self, not. Any of that? Not, I mean, so much of our contortions and posturing and all that is, I mean, back to mortality is a kind of hedge against the fact that we are only here for a short amount of time and, uh, I am, I am personally very comforted by knowing this.

Diane Hullet: I love it. What an incredible way to kind of end. I think here we’ll wrap up [00:25:00] and I think it might be kind of perfect to say that one of the things that I put on my 60 collages that went out is this wonderful Mary Oliver quote that a lot of people are familiar with. Mary Ellen for being a poet, of course.

And her quote from one of her poems is, what is it you plan to do with your one wild, one wild and precious life?

Maria Popova: Oh, who doesn’t love that? And who doesn’t love? Love the soft animal of your body. Love what it loves. You don’t have to walk a thousand miles repenting.

Diane Hullet: Incredible. Well, Maria, I thank you so much for joining me from the beautiful woods and trees, and may you get off the screen and go drink in some nature, and I really appreciate your time and your thoughts, and how can people find out more about your project and your work?

Oh, thank you

Maria Popova: Diane. Um, just the marginality.org, that is where I dwell in the artificial world of screens

Diane Hullet: and I can say it’s absolutely worth signing up for and having this drop in your inbox, I find for me, I don’t [00:26:00] always read the whole thing. ’cause that’s life. And sometimes they get, you read the newsletter, is

Maria Popova: that right?

Mm-hmm. You read the, because that’s just the, I write on the website every day and then on Sunday there’s a little summary that’s. Partial, uh, that some people just

Diane Hullet: read that. Yes. Incredible. So there’s that and there’s the newsletter, which, and, and what I find is if I, even if I don’t always read it, when I read it, it almost always says something that grabs me.

Like I just think, oh, this was the perfect one to open after missing a couple. It’s just really sweet

Maria Popova: because we’re not so unique. See, that’s the evidence. We’re all living the same experience ultimately. Yeah. Just within degrees of separation from. Facts and events of our particular lives. The substrate.

The substrate.

Diane Hullet: I so appreciate your time and the way you look at things and how you hold that really big picture and the smallness at the same time. How you’re there, you know, treasuring your time in the trees, and also continuing to write and make and be, uh, sharing yourself [00:27:00] in such a way that other people can get.

I don’t know, ignited by it. Really appreciate all the what you do.

Maria Popova: Thank you, Diane, and thank you for what you do and for the spirit in which you do it, which is so beautiful.

Diane Hullet: Thanks so much. You’ve been listening to the Best Life Best Death podcast, and as always, you can find out more about the work I do at Best Life.

Best death.com. Thanks so much for listening.

End of Life Doula, Podcaster, and founder of Best Life Best Death.